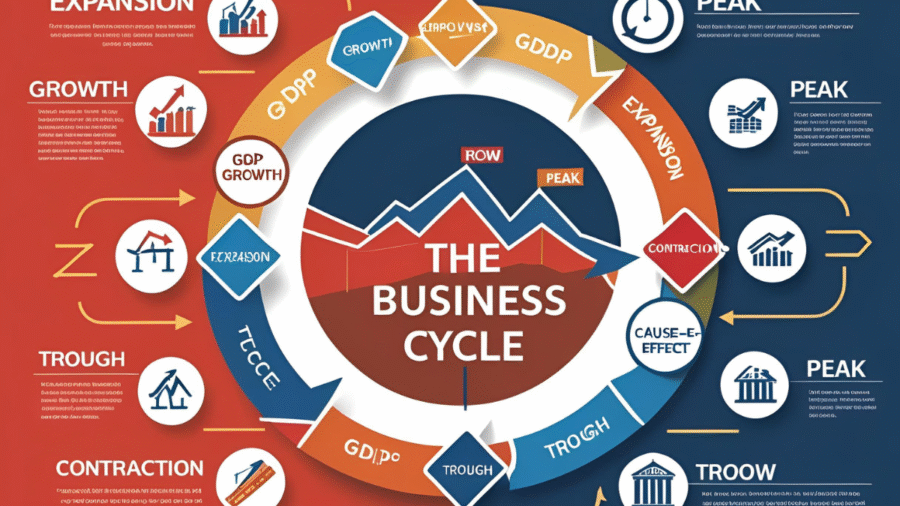

The business cycle refers to the recurring pattern of economic growth and contraction experienced by economies over time. It consists of four primary phases: expansion, where economic activity rises; peak, the highest point of growth before decline; contraction (or recession), marked by a drop in economic output and rising unemployment; and trough, the lowest point that precedes a new expansion.

Understanding the cause and effect relationships that drive these cycles is vital for policymakers, business leaders, and individuals alike. Economic indicators do not shift randomly; instead, each movement in the cycle is typically triggered by underlying causes, such as changes in consumer confidence, interest rates, government policy, or global events, which then produce predictable effects.

For instance, rising interest rates often cause borrowing to slow, which in turn dampens consumer spending and can lead to economic contraction.

This article aims to explore how cause and effect function within the business cycle, providing both theoretical insight and real-world examples. By identifying these linkages, readers can better comprehend economic shifts and make informed decisions.

Ultimately, the piece will answer the question: Which best describes the nature of cause and effect in the context of the business cycle? The answer lies in understanding how interconnected variables create ripple effects that shape macroeconomic outcomes.

What Is the Business Cycle?

Definition and Phases

The business cycle is a fundamental concept in macroeconomics that captures the natural rise and fall of economic activity over time. It includes four distinct phases:

- Expansion: This phase is marked by increasing GDP, rising employment, improved consumer spending, and heightened industrial production. Businesses invest more, and optimism drives further economic momentum.

- Peak: At the peak, economic growth reaches its maximum output. However, this phase also brings inflationary pressures, labor shortages, and overheated markets, signaling an impending shift.

- Contraction (Recession): When the economy begins to decline, we enter a contraction. GDP shrinks, unemployment rises, and consumer confidence diminishes. A recession is technically defined as two consecutive quarters of negative GDP growth.

- Trough: This is the lowest point of the cycle, where economic activity bottoms out. It is often followed by stimulus measures, renewed business investment, and early signs of recovery, signaling a return to expansion.

Historical Examples

- The Great Depression (1929–1939): Triggered by the 1929 stock market crash, the U.S. economy experienced a prolonged contraction with severe unemployment and deflation. Over-speculation and banking failures were key causes, while New Deal policies and World War II-related demand spurred recovery.

- The 2008 Global Financial Crisis: Sparked by the collapse of the housing bubble and subprime mortgage market, this downturn resulted in massive financial institution failures, stock market crashes, and global recession. Government bailouts and central bank intervention eventually stabilized the economy.

- Post-COVID Recovery (2020–2023): The pandemic-induced global recession was marked by supply chain disruptions, lockdowns, and mass unemployment. Recovery began with vaccine rollouts, stimulus packages, and adaptive digital transformation, illustrating how targeted responses can jumpstart expansion after a trough.

Exploring Cause and Effect: What Does It Mean?

In economic terms, cause and effect refer to the relationship between an initiating event or policy (the cause) and the resulting outcome it produces (the effect). This dynamic is essential for interpreting how economies react to different stimuli.

For example, when a central bank lowers interest rates, borrowing becomes more affordable, encouraging businesses to invest and consumers to spend. The resulting increase in economic activity directly affects that policy decision.

This chain of events mirrors familiar real-life phenomena like the domino effect, where one event sets off a cascade of reactions. Another useful analogy is the ripple effect, a single action, such as a government stimulus package, can send waves through the economy, affecting employment rates, stock markets, and even global trade balances.

Understanding these cause and effect relationships helps stakeholders, from policymakers to investors, anticipate economic shifts. For instance, if inflation rises rapidly (cause), central banks may raise interest rates (response), which could then lead to reduced consumer spending and slower economic growth (effects). Recognizing these patterns enhances our ability to respond effectively.

Ultimately, the business cycle is not a random pattern. Each phase results from specific causes and produces predictable effects, highlighting the cyclical yet interconnected nature of economic systems.

Cause and Effect Relationships in Each Phase of the Business Cycle

Expansion Phase

Causes:

- Low interest rates: Encourage borrowing for investment and consumption.

- High consumer confidence: Leads to increased spending on goods, services, and housing.

- Rising business investments: Fuel innovation, production, and job creation.

Effects:

- Job creation: As companies expand, they hire more workers.

- GDP growth: Economic output increases due to higher productivity.

- Inflation pressure: Demand for goods and services outpaces supply, raising prices.

In this phase, the momentum of growth feeds itself. For example, new jobs increase household income, which further boosts consumer spending, creating a virtuous cycle of prosperity.

Peak Phase

Causes:

- Overheating economy: Excessive demand and rapid growth push the economy to its limits.

- High consumer and business spending: May outstrip supply chains and production capacity.

Effects:

- Inflation spikes: Prices rise quickly, eroding purchasing power.

- Tight monetary policy: Central banks may increase interest rates to control inflation.

- Asset bubbles: Overvaluation of assets like real estate or stocks can occur due to excessive speculation.

At the peak, the economy is at its most vulnerable. The imbalances created during expansion, especially rising debt and inflated asset prices, set the stage for correction.

Contraction Phase (Recession)

Causes:

- High interest rates: Reduce access to credit and discourage spending.

- Declining consumer demand: Resulting from job losses or decreased confidence.

- Financial crises: Bank failures or market crashes can sharply curtail economic activity.

Effects:

- Job losses: Companies downsize to cut costs.

- Falling investment: Businesses halt expansion plans due to uncertainty.

- Business failures: Smaller firms or highly leveraged companies often go under.

During this phase, the economy retreats, and government or central bank intervention often becomes necessary to stabilize conditions.

Trough Phase

Causes:

- Bottoming out of demand: The economy hits its lowest point; further decline becomes unlikely.

- Stimulus policies: Governments may implement tax cuts, spending programs, or lower interest rates to spur recovery.

Effects:

- Market stabilization: Asset prices and employment begin to level off.

- Slow recovery: Early signs of renewed investment and spending emerge, paving the way for the next expansion.

This phase is often characterized by cautious optimism. While growth may be sluggish, foundational shifts, such as improved liquidity or innovation, lay the groundwork for future prosperity.

Internal vs. External Causes of Business Cycle Fluctuations

The business cycle is driven by a combination of internal and external factors, each playing a critical role in shaping economic outcomes.

Internal causes stem from within the economy. These include consumer behavior, where rising confidence often leads to increased spending, fueling expansion. Similarly, business investment in machinery, infrastructure, and labor can stimulate production and job growth. Another key internal driver is productivity; when companies adopt more efficient technologies or practices, output rises without proportional increases in costs, supporting economic growth.

However, these same factors can contribute to downturns. If consumers begin saving excessively or cutting back due to pessimism, demand contracts. Overinvestment during booms may result in overcapacity, leading to cutbacks and layoffs later. Declining productivity or stagnation in innovation can also dampen long-term growth.

On the other hand, external causes originate outside the normal workings of an economy. Geopolitical shocks such as wars or trade disruptions can limit access to resources, increase costs, or reduce investor confidence. Pandemics, like COVID-19, can halt entire sectors overnight, leading to mass layoffs and supply chain collapse. Natural disasters, including hurricanes or earthquakes, may damage critical infrastructure, disrupt transportation, and displace communities.

These external forces often trigger swift, profound effects, sometimes exacerbating existing internal vulnerabilities. For instance, a financial system already stretched thin can crumble under the weight of a pandemic-induced shutdown.

Understanding both internal and external causes helps clarify the multifaceted nature of cause and effect in economic cycles and underscores the need for flexible, responsive economic strategies.

Role of Economic Indicators in Understanding Cause and Effect

To navigate the complexities of the business cycle, economists and policymakers rely on economic indicators and statistical tools that help interpret the relationships between causes and effects.

Leading indicators predict future economic activity. For example, the stock market often anticipates changes in corporate profitability and investor sentiment. Building permits signal future construction activity, making them valuable for forecasting expansion or contraction. Consumer confidence surveys also fall into this category, indicating expected spending trends.

Lagging indicators, in contrast, confirm trends after they have occurred. Unemployment rates rise only after businesses begin laying off workers, often during the contraction phase. Similarly, inflation data tends to reflect price changes resulting from prior increases in demand or supply shocks.

Coincident indicators reflect the current state of the economy. These include gross domestic product (GDP), which measures overall economic output, and industrial production, which tracks the real-time performance of factories and mines. These indicators provide a snapshot of economic health at a given moment.

By analyzing these indicators in conjunction, economists can trace cause and effect sequences. For example, if leading indicators show rising consumer sentiment and a surge in building permits, it may signal an impending expansion. Lagging indicators such as rising wages or inflation help confirm that the expansion took hold.

Interpreting these patterns allows businesses and governments to make informed decisions, mitigate risks, and plan for the future.

Government Policy and the Business Cycle

Governments play a pivotal role in influencing the business cycle through fiscal, monetary, and regulatory policy tools. These interventions aim to manage fluctuations and ensure long-term stability.

Fiscal Policy

Fiscal policy involves government decisions on spending and taxation. During a contraction or recession, governments may employ expansionary fiscal policy, increasing public spending or cutting taxes to stimulate demand. Infrastructure projects, tax rebates, and welfare programs are common tools used to inject money into the economy.

Conversely, in an overheated economy approaching a peak, contractionary fiscal policy may be adopted. This includes reducing spending or raising taxes to curb excessive demand and control inflation.

The effectiveness of fiscal measures lies in their ability to quickly influence consumption and investment behavior, though political processes can sometimes delay implementation.

Monetary Policy

Central banks utilize monetary policy to control the money supply and influence interest rates. Lowering interest rates during a downturn encourages borrowing and investment, while quantitative easing, the purchase of government bonds, can further inject liquidity into the system.

In contrast, tightening monetary policy by raising interest rates or selling government assets helps cool down inflation during the peak phase of the cycle. These tools are often more agile than fiscal policy and are essential in shaping short-term economic direction.

Regulatory Factors

Beyond fiscal and monetary tools, regulatory policy also influences the business cycle. Banking regulations can affect the availability of credit, either encouraging or restricting lending. Labor laws such as minimum wage increases or hiring mandates impact business costs and employment dynamics.

Strategic regulatory adjustments can prevent economic overheating or support recovery, while poorly timed or excessive regulation may stifle growth.

Together, these government policies interact with internal and external forces, making them both instruments and respondents in the cause and effect landscape of the business cycle.

Case Studies: Real-World Examples of Cause and Effect in Business Cycles

Understanding the cause and effect dynamics of the business cycle becomes clearer through real-world case studies. These historical events highlight how specific factors can ignite expansion or trigger contraction, and how responses shape outcomes.

Dot-Com Bubble and Burst (1995–2001)

The dot-com era was fueled by explosive growth in internet-based companies. Investors poured capital into startups with little revenue, driven by speculative optimism and the belief in a “new economy.” This led to an unsustainable expansion phase where tech stocks soared, especially on the NASDAQ.

By 2000, reality began to catch up. Many companies failed to turn a profit, and investor confidence collapsed, causing a rapid market contraction. The burst of the bubble triggered a mild recession by 2001, exacerbated by overinvestment, consumer pessimism, and declining corporate earnings. This cycle illustrates how internal factors like overexuberant investment can trigger a downturn.

COVID-19 Pandemic and Fiscal Stimulus (2020–2022)

In early 2020, the COVID-19 pandemic shocked global economies with abrupt lockdowns, halting supply chains and consumer activity. The external cause of a global health crisis triggered a sudden, deep contraction, with unemployment soaring and GDP plummeting.

Governments responded with unprecedented fiscal stimulus, including direct payments, business loans, and expanded unemployment benefits. These expansionary policies helped stimulate demand and cushion the impact, leading to a relatively swift recovery phase in many economies by 2021–2022.

This episode highlights how external shocks combined with policy interventions can dramatically affect the trajectory of the business cycle.

Oil Shocks and Stagflation (1970s)

During the 1970s, geopolitical conflicts—particularly the OPEC oil embargo led to a sudden spike in oil prices. This external shock drove inflation sharply higher, while economic growth stagnated. The result was stagflation, a rare combination of high inflation and low output.

Traditional tools like raising interest rates to fight inflation were less effective, as they further suppressed growth. This event challenged conventional wisdom and forced economists to reconsider the complex cause and effect relationships between supply-side shocks, monetary policy, and economic performance.

Common Misconceptions About Cause and Effect in Business Cycles

Despite extensive research, several misconceptions persist about the nature of cause and effect in business cycles.

Recessions Are Always Caused by Bad Leadership

While leadership decisions can influence economic outcomes, not all downturns stem from poor governance. Many recessions are triggered by factors beyond direct political control, such as external shocks, changes in consumer behavior, or global market trends. Blaming leadership alone oversimplifies the multifaceted causes behind economic fluctuations.

Every Expansion Must End in a Crash

There is a widespread belief that every economic boom inevitably leads to a severe collapse. While cycles do include peaks and contractions, expansions can conclude in mild slowdowns or soft landings, especially with proactive policy adjustments. Not every upward trend must end in a dramatic downturn.

Printing Money Causes Immediate Inflation

Another misconception is that increasing the money supply automatically results in inflation. In reality, the relationship is more nuanced. Inflation depends on various factors, including demand, supply constraints, and economic confidence. During the COVID-19 pandemic, for example, large-scale money printing did not immediately cause runaway inflation due to suppressed demand and high saving rates.

Dispelling these myths is essential for a deeper, more realistic understanding of the true cause and effect mechanisms that govern business cycles.

Why Understanding Cause and Effect Matters for Entrepreneurs, Investors, and Policymakers

Grasping the nuances of cause and effect within the business cycle is not just academic, it is vital for strategic, real-world decision-making across sectors.

Business Decision-Making Based on Cycle Timing

Entrepreneurs rely on economic trends to time decisions such as launching products, hiring staff, or expanding operations. Recognizing early signs of expansion may signal a good time to invest in growth, while identifying impending contractions can help reduce risk exposure. Understanding these dynamics enhances agility and fosters resilience in uncertain environments.

Investment Strategy Alignment

Investors use economic indicators to fine-tune their portfolios. For instance, during an expansion phase, cyclical stocks (e.g., retail, travel) often outperform, while in downturns, defensive sectors (e.g., utilities, healthcare) become more appealing. Knowing which triggers lead to different phases allows investors to align strategies with market momentum, protecting capital and maximizing returns.

Policy Planning and Crisis Response

For policymakers, a firm grasp of cause and effect is essential to crafting effective fiscal and monetary policies. Recognizing the early causes of inflation or recession helps guide timely interventions, such as adjusting interest rates or initiating stimulus packages. Anticipatory action based on sound cause and effect analysis can stabilize economies before crises escalate.

In essence, understanding these relationships empowers key players, business leaders, investors, and policymakers to act proactively rather than reactively, turning insight into competitive and societal advantage.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

What is the best example of cause and effect in a business cycle?

A classic example is when a central bank raises interest rates (cause) to combat inflation. Higher rates make borrowing more expensive, which reduces consumer and business spending (effect). As a result, economic activity slows, sometimes leading to a recession if the contraction is significant. This illustrates how policy decisions directly influence economic outcomes.

Why does understanding cause and effect matter in economics?

Cause and effect analysis enables economists and decision-makers to anticipate trends and craft informed strategies. For instance, if policymakers detect early signs of economic overheating, they can act to cool it down through interest rate hikes or tax adjustments. For businesses, understanding these dynamics helps avoid costly missteps, like expanding during a downturn or cutting back during recovery.

Is the business cycle predictable through cause and effect analysis?

To some extent, yes. Economists use leading indicators and historical patterns to anticipate shifts. However, unpredictable external shocks like pandemics, geopolitical crises, or technological disruptions can derail predictions. While patterns help, certainty remains elusive, and flexibility is essential.

Can individuals influence the business cycle?

On an individual level, the impact is limited. But collective behavior, such as consumer spending, saving trends, and investor sentiment, significantly influences demand and investment flows. Over time, this aggregated activity can affect GDP growth, inflation, and employment, all of which play key roles in the business cycle.

How do central banks use cause and effect to manage the economy?

Central banks, like the Federal Reserve, use monetary policy tools to manage economic stability. By raising or lowering interest rates, they influence borrowing costs, consumer spending, and investment. For example, during inflation, higher rates can slow demand and curb price growth. This is a prime example of deliberate cause and effect manipulation to guide the cycle toward stability.

Conclusion

The business cycle is far more than a series of ups and downs; it is a complex web of causes and effects, where individual decisions and global events intersect to shape economic outcomes. Each expansion or contraction is rooted in triggers internal or external that ripple across sectors, influencing growth, inflation, employment, and more.

Through this exploration, we have uncovered how indicators, policies, and behavioral shifts combine in a dynamic, interdependent system. Recognizing these patterns allows for data-driven analysis, better forecasting, and more strategic choices in business, investing, and governance.

So, which best describes the nature of cause and effect in the context of the business cycle?

It is a dynamic, interdependent relationship where triggers in one part of the economy generate ripple effects that shape the broader economic landscape.By embracing this mindset, we move from passively observing economic tides to actively navigating them.

Add a Comment